Lotus & Michael Perspective 5-2023: A Game Changer in four parts

(The article under separate cover is translated into Simplified Chinese)

I. The situation for Chinese textile/apparel exporters in 2023 and why it is what it is. What is the current textile and apparel situation in China?

II. Who is W. Edwards Deming and what did he tell the Japanese in 1950?

III. What needs to change in China to rebuild China’s reputation, respect and business?

IV. If not, will there be a Reckoning for China textile and apparel like there was for the US Auto Industry?

Article Abstract: Textile and Apparel business in China is suffering badly. Some or all of the following factors can be held responsible: 1. Political relations and the continuing Tariffs; 2. China’s reputation for cheap and poor quality product which is, at least partially, justified by evidence; 3. Sluggish domestic demand due to the lockdown and poor economy in China; 4. Due to some or all of the above, significant resourcing to alternative countries such as Vietnam.

In this article, we suggest that the only long-term solution for China is to rebuild its reputation for quality product and fashion innovation, just as Japan did in the 1950’s using the lessons of W. Edwards Deming’s teachings as a platform. Combined with this, China factories need to build their own brands which a. don’t scream Cheap and b. stand up to other international brands in style and quality.

But, China factory owners are resisting change, starting to panic and are lost for any solution except to find someone who may sell their product for commission. But, what would they be selling other than “Cheap China?”

Finally, we predict that, if some factories don’t lead the way to a new direction for China, the Chinese textile industry will crash and burn or, at best, be relegated to the mass market in such outlets as TJ Maxx and Walmart. Part of this is due to the bifurcation and consolidation of the US retail economy: The middle level department store base is disappearing, leaving only either competition for the mass market at rock-bottom prices or premium and luxury brands sold DTC or on platforms like Net-A-Porter and FarFetch. In addition, many new and innovative brands are appearing almost daily. The only Chinese online alternatives to those platforms are SHEIN and TEMU, which are by nature cheap and poor quality, and the innovative Chinese brands are rarely seen by overseas customers.

The Chinese textile industry will have to have a Reckoning, just as the American auto industry did in the 1970s and 1980s (as described by David Halberstam in his Pulitzer Prize-winning 1986 book): The world has changed; the way you did things and the things you got away with in the past are gone. If you don’t face the reality of the world today, you will also be gone.

I. The situation for Chinese textile/apparel exporters in 2023 and why it is what it is. What is the current textile and apparel situation in China?

The China textile and apparel business is in trouble. After more than 20 years, since China was admitted into the WTO and quotas were abolished, there isn’t room for one more manufacturer to do business with US customers and export their product, getting rich (comparatively or really) in the process. Here is a peasant economy that was transformed almost overnight into a global powerhouse, ascending to the #1 position as the world’s factory. Just open a factory, sell something (it doesn’t have to be great), and you will have lots of customers.

Led by Walmart, who buys 70-80% of their product from China, immense volumes of cheap goods filled American stores and sold on websites. Department stores like Macy’s ran to China to get into the cheaper-than-thou game, rather than stick to their middle-class roots. So, in what seemed like the blink of an eye, everybody wanted to buy shit from China (that word used qualitatively). What happened on the consumer side was, confronted by a sea of cheap shit everywhere, the average consumer (not just the struggling ones who needed to buy cheap) flipped their value proposition from price is determined by value to value is determined by price.

Let’s look at the numbers, which we will say up front are deceiving:

For 2021, according to the US Department of Commerce report:

“In 2021, China remained the major source of U.S. imports of Textile Products. In 2021, U.S. imports of $50.3 billion of Textile Products from China constituted 32.6% of the total U.S. imports of Textile products.”

And 2022:

“In 2022, China remained a major source of U.S. imports of Textile Products. U.S. imports increased by 6.7% ($3.4 billion) from $50.3 billion in 2021 to $53.7 billion, constituting 29.7% of the total U.S. imports of those commodities.”

All good, right? We see several issues: 1. 2022 was the first non-pandemic year so it stands to reason imports should go up (they were $538 billion in 2018 so overall they were just reaching pre-pandemic levels; 2. Had China had the same piece of US imports in 2022, it would have had $1.1 billion more business; 3. Based on the numbers given, US imports of those commodities increased 18.2 percent from 2021 to 2022, so China’s increase was indeed a smaller piece of the pie; 4. These numbers reflect what was received in 2022, so based on the planning cycle of 4-6 months, much of the goods were ordered in 2021.

Any way you look at it, despite the increase, there is a clear erosion of textile and apparel imports from 2021 to 2022. Orders received in 2022 and delivered in 2023 will show a further erosion.

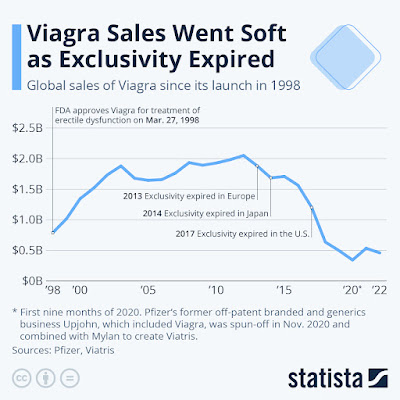

Here’s the worst part: Clearly China factories are shipping goods just to ship goods and are sacrificing price and profit. Take a look at this:

Apparel Imports from China were 35% of the quantity but only 22.2% of the value. On the other hand, imports from Vietnam were 15.9% of the quantity and 18.4% of the value. What does that mean to you? Cheap China is getting cheaper while Vietnam is commanding higher prices.

Now, we should have an idea of what is happening in the textile and apparel sector from China and why Chinese manufacturers feel lost and desperate. This will only get worse.

So the question if you are Chinese manufacturer is (or should be), “What should I do?” It is clear that the definition of insanity applies here: trying to do something the same way twice and expecting different results. China and China’s economy needs different results, especially in the textile and apparel industry. The 10% of imports from China that apparel and textile represents cannot erode without significant effect on the economy and employment. We can guarantee that, based on clearly established patterns of the industry (not just in China) that the workers will bear the brunt of any reduction; the owners are not giving back anything from their bank accounts.

Finally, weak economic growth and disruption in China has a significant effect on the world economy.

The rest of this article will build a case for a sea change in China’s apparel and textile industry, the same sea change that Japan made to transform the tagline of “Made in Japan” from cheap to one of the world’s best.

Those who read this and know China will wonder whether the culture and experience since Deng Xiao Ping declared that some people should get rich first is so embedded at this point that it minimizes or eliminates the possibility of positive change. We believe it can happen, led by the younger generation, the sons and daughters of the people who got rich first and the easy way. But it won’t happen until the older generation steps aside AND the government lets it happen.

Next, we take a look at what happened starting in 1950 Japan, led by W. Edwards Deming, which led to Japan’s current position on the world’s quality product scale. THIS is the example China should follow.

II. Who is W. Edwards Deming and what did he tell the Japanese in 1950?

(For more details about Deming and the development of his legacy, watch the video here.

After teaching wartime courses to US forces on quality control during WWII, Deming was invited to lecture on Statistical Quality Control in Japan by the Union of Japanese Scientists and Engineers (JUSE). His lectures gave rise to development of effective statistically-based quality process systems in Japan and the framework for innovation now known as PDCA (Plan- Do- Check- Act).

Deming gave a six-part lecture series which contains many of the concepts and understandings that changed Japan and are still followed today. The same JUSE started awarding a “Deming Prize” to the outstanding firms in 1951.

Here are some highlights of the series:

His opening- "We are in a new industrial age created largely by statistical principles and techniques. I shall try to explain how these principles and techniques are helping Japan to increase her export trade.”

Super important and super simple: “Quality had to happen at all stages in the "chain

of production.”” This means, quite simply, that basing quality control on final inspections after the damage has already been done and value added to an unacceptable product is a waste of time and money.

What later became part of Deming’s famous 14 points was “improved competition position,” giving the customer a key role in quality management and improvement.

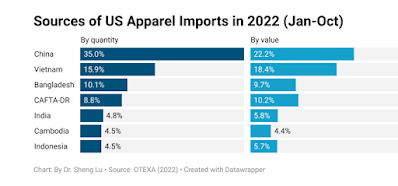

Deming changed the old way of Design it-Make It-Try to sell it to what is known as PDCA:

1. Design the product (with appropriate tests).

2. Make it, test it in the production line and in the laboratory.

3. Put it on the market

4. Test it in service through market research. Find out what the user thinks of it, and why the nonuser has not bought it.

5. Redesign the product, in light of consumer reactions to quality and price.

6. Continue around and around the cycle.

I would refer to this concept as “make what you can sell, don’t try to sell what you make.” This has been and is Amazon’s paradigm and is a big contributor to their success.

Two illustrations from Koiesar’s article are material here:

Note that the quality process here is process-based not result-based. What this means is that by the time the product is finished and ready for shipping, it has already been tested- materials, and at various times during the manufacturing process. So final inspection is, for the most part, a formality.

Why is this better? Because problems can be identified before more material and labor is put into them, and problem processes or workers isolated. (Note that the overwhelming majority of apparel suppliers and buyers use AQL, which is a statistically-based FINAL inspection process that takes place when 80% of the product is ready for shipment).

I tried to implement Deming’s style of control when I was importing car alarms from China in the early 90’s, and in every factory that I worked with as the VP of Sourcing for GoldToe Moretz, a socks company. It was like trying to teach a chicken to dance ballet. Finally, I visited one factory in India that was conducting a full inspection after knitting. The way socks are made, 90% of the production is focused on knitting; all there is after that is closing the toe, boarding (shaping) and packing. Of course! Why spend money, time and labor to process the sock and only inspect after the entire process is finished? This is the essence of Deming’s quality philosophy.

Next is graphic representation of the PDCA cycle or “Design Cycle”:

This is the essence of the difference I mentioned before, making what you can sell as opposed to selling what you can make (or have made).

Also note that this is a continuous loop, so for this process to be successful, it must be something that is committed to for the long term.

So why doesn’t everyone do this? It’s so simple and makes great sense. The main reasons are because a. it takes more time, b. it costs more, and c. It requires patience and commitment to this process. Most factories, not just in China, and buyers are not willing to follow this process, or management won’t facilitate it, opting for throwing shit against the wall and shipping what sticks.

Deming’s first lecture in 1950 stated that there should be: “The integration of the suppliers into the production system and the need to take a shared responsibility for their quality, instead of treating them as outsiders and antagonists.” This is a big issue that is not relegated to China, but is a prevalent attitude of buyers who refer to “the factory” as if it were an inanimate object.

When this stops is when the factory produces something whose quality is undeniable and unimpeachable and where they don’t compromise anything for an order.

Deming continues to be studied because his system is logical and it works. Those who never heard of Deming and heard the words “Statistical Quality Control” and “Total Quality Management” without knowledge of Deming himself and his principles will mistake it for a statistics-dependent methodology; that would be very wrong. Yes, Deming believed that statistics play and important role in Quality and Improvement management, but he by no means was a blind follower of numbers; conversely, he emphasized that “the control chart is no substitute for the brain” and that "The best protection is afforded by acceptance sampling

done in conjunction with quality control at the manufacturing plant. It is not economical to try to get a good product by inspecting a lot and taking up only the best ones."

I was lucky enough to have Deming as a professor for a course at NYU Stern in the mid-1970’s. While I now regret not absorbing more of what he said, it is clear to me that the striking aspect of his teaching and his message is that you didn’t really need to take notes because it all made such common sense.

The result of Japanese manufacturers absorbing and incorporating Deming’s lessons is history. Today, rather than representing cheap product, Japanese products justifiably compete for the title of “world’s best” in many areas. Material and manufactured product are unquestionably superior, and command a superior price. Customers pay for quality, which builds value, and are passionately loyal to brands that provide it for them. I could make a list from my own experience, but I believe you know what I mean..

Is that the case for China? Should it be? Can it ever be? If it should and can, what changes need to be made for it to be successful?

III. What needs to change in China to rebuild China’s reputation, respect and business?

Let’s do two things first: 1. Look at the situation in China now 2. Look at the cultural foundation and see if there is a strong tradition/basis to fall back on or are we stuck with the now.

Where are we now in China? As I wrote in 2017 on my blog www.isourcerer.com in the article, “China Quality- Good Enough is Not Good Enough”, there is no internally-generated quality standard for most factories (I have visited many hundreds), except for that which is generated by customers. Passing inspection and shipping the product only requires “good enough.”

So what is the problem with that? Mainly, it serves the evaluation of “cheap china.” And secondarily, it discourages investment in something better which is internally generated. Factory owners think, “Why should I spend money to improve if the buyers accept what I am shipping now?” Here’s the answer to that question with another question: IF your buyers ACCEPT shit because they EXPECT shit, is that good enough for you? Buyers don’t pay premium prices for shit, and when some factory or country comes along with cheaper shit, you lose. Some companies, like Temu and Shein, have correctly diagnosed that the American consumer WILL accept shit as long as they pay shit prices. This perpetuates the story. So cheap china ACCEPTS the title of chief purveyor of shit, because It is the only way they know of to compete with other countries with lower labor costs AND it is what they have been doing all along during the time you could ship any form of shit and be successful.

That philosophy may get some orders, as long as there isn’t another factory or country with CHEAPER shit.

Price is a race to the bottom.

Was China always the world’s leading provider of shit? Does it have a tradition of craftmanship and quality to fall back on as Japan does?

Japan was able to instititutionalize Deming’s teaching because it aligned with an ancient tradition which is called Monozokuri. “ Literally translated, it means to make (zukuri) things (mono). Yet, there is so much meaning lost in translation. A better translation would be “manufacturing; craftsmanship; or making things by hand.”

There are so many stories in our lives to see and understand Monozokuri. It is stamped on every Japanese product we buy. For example, a 750L bottle of 12 year old Yamazaki Malt Whiskey sells for $210.99; a decent Scottish Single Malt like Balvenie Double Wood can be had for 1/3 of the price of the Yamazaki. So why do people purchase the Yamazaki? Is it three times as good as the Balvenie? From personal experience, I can say that it is because: 1. It is, in fact better, as near to perfection as single malt gets and 2. The aspirational dimension of drinking something that special.

So is China, one of the world’s oldest recognized cultures, devoid of a quality tradition like Monozokuri? OR has it been swallowed up in today’s race to make shit?

When you serve dinner on plates made by Royal Copenhagen, Wedgwood, Villeroy & Boch etc. it is sold to you as “fine china.” IN fact, this dinnerware has nothing to do with China except the origin of that product was China—during the Tang, Qing, dynasty etc. where they made bone china (partially from cow bone) like blood red, Jihong or blue and white porcelain antiques from those eras. But, as my wife Yuting Zhang bemoaned in her 2018 article published on the I, sourcerer (www.isourcerer.com) blog, “The Name is Fine China; so Why is there no Chinese Brand?” none of the premium China on the market today is actually FROM China.

The answer behind this is sad, but points us in the right direction for solving this problem. There is, in fact, a tradition in China called "造物" (zào wù) which translates to “creation.” It was this tradition which was responsible for much of what we take for granted in today’s world. ChatGPT describes this tradition as compared to Monozokuri:

“It's worth noting that while the term "Monozukuri" is often associated with Japanese manufacturing philosophy and culture, China's own tradition of craftsmanship and manufacturing aligns with similar principles of precision, attention to detail, and the pursuit of excellence. The Chinese term "造物" captures the essence of this tradition, emphasizing the act of creation and skilled craftsmanship that has been valued throughout China's history.”

When did that history take place? As early as the Han Dynasty (206 BCE- 220 CE, innovations like the compass, gunpowder and papermaking took place; The Song Dynasty (960-1279) created advancements like movable type printing were created; the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) saw a great fleet and the Great Wall built; the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) saw the first use of vaccines, improvement in agricultural tools and advance mathematical knowledge.

So what happened? These developments were overshadowed by an antiquated and fractured political system which isolated itself from the world and lost its control to the Western powers whose only achievement was the deployment of seagoing ships and advance weaponry. Japan, on the other hand, united the country during the Meiji Restoration in 1868.

Then, Deng Xiao Ping, with all good intentions and rather than fall back on China’s unique tradition, encouraged people to be practical and do what worked for other countries. “The cat that catches mice is a good cat.” Too much, too fast. Many Chinese, who had been mired in poverty and anonymity, saw an opportunity to move out of their class, at least financially, quicker than ever. And it was easy, with the US and Europe as willing customers. So it was damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead and quality was crushed under the need for speed and greed.

So here we are, with Temu and Shein gaining huge international popularity through their seemingly endless pocketbooks and becoming the flagship of Cheap China. And thousands of factories (Probably including those that sell on Temu and Shein) suffering precipitous drops in business or profit or both.

What has to happen? From this end, our position is something needs to change (what will happen if nothing does will be discussed in the next section). Since labor costs are increasing in China and the working population is aging and shrinking, there is no chance to revive the naïve history of the last twenty years. But China can be two important things to the international marketplace: 1. The JIT (Just In Time) resource with still huge capacity for materials and production and 2. The location for growth of artisanal production in the spirit of zao wu.

It is the last one that we believe is what needs to be the focus of all, but especially textile and apparel manufacturers in China: Create their own brands that stand up to international competition, yet fully utilize the resources that are still strong in China: skilled labor, quality materials, coupled with fast and efficient production, short transportation leadtimes.

The how and why of this strategy depends on the industry but, as strange as it may seem in the red ocean of digital players, there are still huge holes and opportunities because most of the products online are echoes of each other, ho-hum and not worthy of customers’ attention. So the factories will ask, what can I do? The answer:

1. First, STOP. Put your ego away for a while.

2. Understand and accept the fact that the situation has changed; the days of easy money and good-enough quality are gone;

3. Adopt a quality standard that is great, not just “good enough,” based on your pride as an artisan, not a wholesaler of cheap goods; something you can be personally proud of.

4. Don’t expect to pay someone commission to sell what you made; make what your customer wants to buy;

5. Accept the fact that you need to spend some of the money you made so easily on future growth;

6. Don’t be in a hurry; it will definitely happen, but not tomorrow or the next day;

7. Call on the spirit of zao wu and the team efforts of talented people (not just in China, especially in the target market countries like US) to create a Unicorn;

8. Understand that you should be making a product whose price is determined by its value, not the other way around;

9. Let the product speak first so the fact whether it was made in China or not becomes invisible, as is the case with Samsung and LG made in Korea or Kia or Toyota etc.

10. Operate under the main goal of Blue Ocean Strategy: Make the Competition Irrelevant

11. Remember that your brain is your moat; even if competitors want to copy you (Good! Sun Tzu—Shape Your Opponent), they can’t copy your creativity.

12. Obey the (Chinese) strategy of Salami Slicing or The Frog in Warm Water- By the time the competition realizes that you are a threat, it is too late.

13. Read the next section for the consequences if you don’t heed the above.

This is not just a paradigm change, but a game changer, for Chinese entrepreneurs and manufacturers. There is a unique history, tradition and an infrastructure to support this change. If you were a manufacturer in say, Bangladesh, you wouldn’t have any of this to lean on, so your road to success with this strategy would be that much harder.

Most important, as the Japanese did, there has to be an emerging national spirit of pride in Chinese Manufacture as the site of the world’s oldest tradition of creativity and innovation. This has to be an initiative of the people, not Beijing. This is people, not government.

Further, these changes require investment and patience. They will not happen overnight and they will not happen if the only thing in the manufacturers’ mind is to sell what they make and pay some poor soul commission to try to peddle it. They need paid apostles: those who are also passionate about the goals but who are fairly paid for their work; no risk, no reward.

What will happen if nobody pays attention and nothing changes? There will be a Reckoning.

IV. If not, will there be a Reckoning for China textile and apparel like there was for the US Auto Industry?

What is a “Reckoning?”

According to Collins Dictionary, it is “if someone talks about the day of reckoning, they mean a day or time in the future when people will be forced to deal with an unpleasant situation which they have avoided until now.”

It is the same consequence the US Auto Industry faced in the 1970’s, according to the great book by David Halberstam of the same name.

What happened then?

As Halberstam describes in his opening chapter, “Maxwell’s Warning,” in 1973 Charley Maxwell tried to warn the automakers in Detroit that a sea change in oil prices was coming, thus their gas-guzzling big cars would be uneconomical compared to Japanese cars and German cars. He had concluded that the world “had changed and was going to continue to change.” Not only did they not heed his warning, but he never got and audience with or the attention of the decision makers. In Halberstam’s words, “he had not even gotten across the moat. Detroit was Detroit, and more than most business centers, it was a city that listened only to its own voice.”

It was a serious case of denial that has brought down many iconic businesses in the US even until today, such as Sears and ToysRUs. Halberstam tells us, “They believed that tomorrow would be like today because it had always been like today and because they wanted (emphasis mine) it to be like today.”

This attitude resulted in an unprecedented loss of market for US domestic auto industry, and a great growth story for foreign brands, led by the Japanese. Let’s make a corollary here with the situation in 2023 for Chinese manufacturers, especially the textile industry. To begin, let’s read the ending paragraph of Halberstam’s book (substitute Chinese for American). He speaks of the emergence of immigrants, especially Asian immigrants, who saw the possibility of a regenerative life in the US, as opposed to native Americans who took it for granted:

“The other respect in which America was ill prepared for the new world economy was in terms of expectations. No country, including America, was likely ever to be as rich as America had been from 1945 to 1975 (my comment: China?), and other nations were following the Japanese into middle-class existence, which meant that life for most Americans has bound to become leaner. But in the middle of 1986 there seemed little awareness of this, let alone concern about it. Few were discussing how best to adjust the nation to an age of somewhat diminished expectations, or how to marshal its abundant resources for survival in a harsh, unforgiving new world, or how to spread the inevitable sacrifices equitably.”

These are the results of the Reckoning that America faced in the 1980’s and they are terrible. Take a look at the following numbers:

Since foreign-owned auto companies relocated most of their US production to the US itself, and approximately 25% of the domestic auto production comes from NAFTA partners, it has not been a total loss for the American economy. That said, it is still a very sad story for the once-dominant American auto industry and one China can learn from.

What will be the number for Chinese textile manufacturers in 5 years? The world moves much more quickly than it did in the 20th century, so it is not necessary to wait 50 years, or even 20, for results.

Does this mean that Chinese manufacturers have to open factories in the US or NAFTA or other FTA partners in the Western Hemisphere? Maybe. This type of action would be in line with what I suggested earlier: doing something different than what had been done before because you recognize that the situation is changed and will never be the same again; therefore you need to radically change your strategy. Mostly it involves following the example of brands like Toyota, Samsung, LG etc. that have not only dominated the US market but have made their foreign origin a non-factor. This includes hiring capable people in the US who understand and can restore companies’ and consumers faith in Chinese product.

And what about the Chinese Currency? There was a time when China was called a currency manipulator because it intentionally pegged its currency to the USD to promote exports. The bet then was that the currency would materially strengthen against the USD if it were freed. I wonder what would happen if the RMB were left to free float today? Maybe just the opposite, which would be a further disaster for China. Would you buy in?

The most important lesson to be learned is that which this article is about. Since there is no Deming to teach and inspire us, Chinese factories need to look to his teachings and the results from those that followed them, like the Japanese to lead to a sea change that lays the groundwork for success in the future. This would be a productive change for China.

Again, two main lessons from Deming are: 1. Quality control to a standard of zero defects; 2. Adopt the PDCA philosophy and methodology, which signals a paradigm shift to make what the customer wants, as opposed to selling what you have. It means a change in philosophy, but, as said earlier, not one that is non-existent in China and Chinese culture.

It actually means a spiritual and actual return to China’s Golden Age of innovation. There are still companies in China, like Zhangxiaoquan (knives and cutlery of the finest quality) and Jingdezhen (beautiful cups) that have uncompromising quality standards and command a commensurate price. If this means they don’t reach the pinnacle of volume, they are happy to accept. This should be the paradigm of all Chinese producers who want to grow their business in a sustainable manner.

The last word should be the distinction that Lotus is fond of making, which applies to the Japanese auto companies in the 1970’s and 1980’s, and maybe still today: Between entrepreneurs and businessmen.

When the Japanese started to make an impact on the US market, some 20 years after Deming went there, they were entrepreneurs, marketing according to the PDCA system. They tested the market, revised their product and service accordingly, and continued to refine their offering until today.

We hope that system can be widely adopted in China, which would indicate a sea change in mindset. From our knowledge of many factories, the current owners, spawned from the Deng Xiao Ping era and China’s record growth, are “old school” and cannot pivot; it will have to be their sons and daughters, maybe even their sons and daughters, who understand and implement the change in a widespread fashion. This is the game changer we are looking for.

Problem is, by that time the situation will continue to erode and textile and apparel manufacturers will find themselves with a permanent loss of market share, just as the American auto manufacturers have; or worse, with the same fate as Sears and ToysRUs.

What we need and what we are looking for are a few souls to start the fire.

Then, in the future, the Great Reckoning can be called the Great Awakening.